Explorative,

creative learning is

important. But it can be very hard to make happen, especially for those (most) of us parents who were raised in a conventional coercive school system. Two of the biggest issues we have run up against are my own fears of kids not doing enough, and my kids' difficulty in finding inspiration. So over the years I've come up with a few strategies for nudging them along without coercion, and I thought I'd share them with you.

*A note on curriculum: While I'm aware that many of my readers follow a purchased or school-provided curriculum, I think it's important to remember how very little these guidelines actually matter. If somebody says your child should learn the names of all our local planets in grade two, so you ensure memorization of these names and planet features, what is the likelihood that your child will remember them ten years later? Not much, unless the child was and continued to be interested in those facts. However, if the child never knew the names until he was in his twenties, and then took it upon himself to explore and discover them, he'd probably remember them simply because he cared more. It's like that with everything from reading to math skills to social skills. When we perceive a personal need or desire to learn, we do. There is indeed a progression of suggested skills in most curriculum packages, but I have learned from my children that skill #7 doesn't need to be preceded by a teaching of skills #'s 1-6. When the need for them arises, they'll fall into place. And depending on the kids' learning styles, the way things fall into place will differ.

I suppose this article will be useful for different people in different ways. If you're a teacher or a homeschool parent you'll want to adapt to your curriculum; if you're an unschooler or a teacher of self-directed learners, you might want to read this article with the kids and see how or if they'd like to engage with these ideas. Whatever you do - enjoy! And I'd be happy to hear about other ideas in the comments.

The essential thing to keep kids interested is to keep the subject

matter relevant. Unless a child has some personal context for ancient

Rome or cell biology, it will be of little interest. So start with

things that matter. And that's home. Family. Direct experiences the

child is having. And you can't provide the experiences to augment the

ideas you're trying to teach; you have to provide the experiences first -

or better yet, work with experiences the child already has and allow

those to lead to new and different places.

Now for the project suggestions:

Books!

I have to start here because honestly there are so many amazing books out there that bring our own local spaces to life with wonderful stories and images. From local mythology to children's picture books to adult fiction and non-fiction, there is very little as wonderful as exploring your own world through a passionate author's eyes.

Activities to do with the books include:

- create maps of the places listed in the books

- write fan-fiction based on the books

- create dramatic productions based on the characters or even directly adapted from the books

- create a tour-guide to the area shown in the book

- take the book to the specific location where the story takes place and read it there

- replicate the foods, crafts, or other things mentioned in the book

- ...etc. Let the book and your kids' creativity lead the way!

|

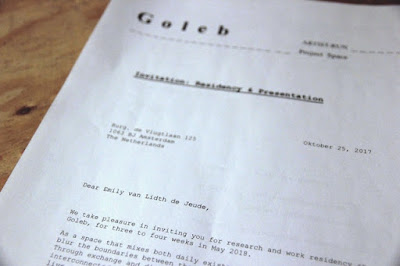

| This was my kids' giant hand-drawn map of Haida Gwaai, inspired from print-outs, photos, and the amazing book, the Golden Spruce, by John Vaillant. We also wrote to John, since he's a local author, and thanked him for his wonderful book. |

Local Map Exploration

Get a very good local map (printed version is better than digital) and hang it on an often-seen wall. Good sources for such maps are often geological survey departments, hiking or orienteering groups, a map store, or

Backroad Mapbooks, here in Canada. Find a map that has topography, creeks, trails, historical and geological features... whatever interesting things you can find. If the best maps you can access are online, find one and have it printed large-scale to hang on your wall, or laminated for table- or floor-use.

The key here is local. You want to find a map local enough and large enough that you can see the location of your house or building as distinct from your neighbour's. This is what makes things matter. You can draw yourselves onto the spot where you live.

The obvious is to start exploring things you find on the map, and letting those explorations lead to new discoveries, but we've also had many fun map-games, in addition to the exploring. Sometimes we got out little toy cars and drove them around on the map, telling stories as we went; sometimes we made map-board-games, where we set out missions to accomplish on the map, and used dice-throws to determine inches traveled between places. For example: Leave home, go to the store to buy popcorn, check the mail, pick up a parcel from the post office, go to friend's house to pick them up, and take them to the beach for dinner. First person to arrive at the beach is the winner! Although in our non-competitive household, we ended up picking each other up from the road as we went by.

Another idea is long-distance treasure-hunting, using the map as a first clue and travel-aid. We once set up a fabulous mile-and-a-half treasure hunt for our daughter's birthday cake. The hunt began in the daylight, and by the time they found the cake it was dark, necessitating a hike up a candle-lit trail to the cake in the dark woods. Of course my job was to hike the cake in before they arrived, turn on the electric-tea-light-lit trail markers, and then light the cake just as they arrived. And yes - forest fires are a concern here. But it was well into the rainy season by the time we did this.

Local Resource History and Manufacturing:

Things don't just come from a store! Hopefully you already shop locally as much as possible, so follow some of those leads. If you see locally-produced goods for sale, see if you can arrange for guided tours of the places they're produced. Sometimes you can even get involved in the production or tending at the facility. Some ideas of this sort are:

- farms (we once watched a lamb being born at the farm where we buy our lamb-meat!)

- dairies, including the grazing areas for the cattle or goats, if possible

- broom-makers, milliners, glass-blowers, shoemakers and other specialty shops

- breweries, candymakers, and other food production

- cement factories

- the local dump or recycling facility - we did a tour of ours once and it was fascinating!

- mines (including abandoned mine-adits like the one near our house!)

- fisheries and fish-processing plants

The list goes on and on of course... look at where the objects you buy come from, and see if you can visit! We once discovered that the wheelbarrow we own (the most popular affordable wheelbarrow at our local shop) actually is made in the small Dutch town where my grandmother and father lived! Since it's half-way around the world, we haven't been there, but we sure looked them up on Google Maps! You just never know what discoveries this exploration may bring to you.

Google Maps or Google Earth:

Well where to begin?! Obviously just exploring Google Maps (or Google Earth if you want to get fancy) is a fabulous activity on its own - no guidelines, nobody hanging over your shoulder, handing over expectations or asking you what you learned... just discover. We've found some of the most amazing things, from unknown (to us) remote modern day civilizations, to craters, migrating animals in the Savanna, and even shipwrecks. We also toured our own community in Streetview and found people we know!

But I promised you some guided activity ideas. Here are a few.

How about guided Streetview tours? Yep! Google offers those:

Google Maps Treks

You can also use Google Maps to create your own customized maps on

My Maps. Consider using this tool for special projects that you set up for your children or better yet that they make for themselves. Some ideas to consider: a treasure-hunt, a map of local pets or babysitting clients, a road-conditions map, or a forest or wilderness observation/conservation map (make field trips into specific areas and detail the condition of the area, animals observed, or places of interest on an interactive map to share with others). You can also use My Maps to track where you've been on your local (or global) adventures! These maps can have multiple contributors, which opens the opportunity for groups of kids to work together on creating useful and interesting maps that are meaningful to them in a local and social context.

One activity I set up for my kids was a Google-based story writing project. I set up a few tables like the one below, providing just enough information for some Google-maps searches that led them to a few vaguely or directly-related places around the world. Each of the sets of places followed some kind of theme or story-line I had in mind, but I didn't provide this to my kids. Their mission was to fill in the table as much as possible or desired, and then to write a story using all or most of the places, things, and details from the table. Don't get too attached to your own ideas that went into compiling the table - if you leave enough information out and encourage your kids to really let loose creatively on a regular basis, the story your kids produce will likely be nothing like the one you had envisioned. Your kids might even discover a different place, business, or item at the coordinates you've given. That doesn't matter - this activity has no wrong answers. There's sure to be something interesting to come out of any solution to the puzzle.

Obviously, this does take a bit of prep-work, but I have to admit it was fun for me. :-) The table below is an example, but if you use this idea, I encourage you to tailor the table to suit your own needs and interests. I usually had the Place Name column and the Address/Coordinates column, but often had other things like "altitude", "local recipe", or "person who lives there", which sometimes included real people in our community, famous people, or scientists or employees whose names I found on websites of the places I listed!

| Name of Place | GPS coordinates or

Street Address | Person, plant or animal | Weather forecast

(or other detail) | Other notes |

| 201 Kicking Horse Ave P.O. Box 148

Field, British Columbia

Canada |

| -1C (31F)

snowing |

|

| 51.430112, -116.462598 | phyllopod |

| Use satellite view |

| Highway 838 Midland Provincial Park Drumheller, Alberta Canada |

|

|

|

Maotianshan Shales

|

| marrella |

|

|

| Youpaotai Rd, Nanshan Qu, Shenzhen Shi, Guangdong Sheng, China | A small weed growing from a crack in the pavement |

|

Use satellite view! |

Spoiler Alert! If you are wondering what this table is about and don't want to go research those locations, here they are, in order that they appear on the table. This will give you an idea of the theme I was following, on this table:

- Burgess Shale Geoscience Foundation

- Mt. Field (location of Walcott Quarry; Cambrian fossils)

- Midland Provincial Park (contains Royal Tyrell Museum and is near to Fossil World)

- Maotianshan Shales (Cambrian shales in Chengjiang, Yuxi, China)

- Chiwan container terminal in China

And maybe story-writing isn't your or your kids' thing? Maybe this info will feed into a fabulous painting or sculpture; maybe it will become a theatrical production or a YouTube comedy show. The idea is to give some inspiration and then step back to allow kids to run wild and see what comes out. So work with it until it works for you.

Exploring Google Maps is a bit like air-travel, so here's one last idea, while it's on my mind: get the free flight simulator,

GeoFS, and fly from airport to airport, discovering new places as you go! My son has spent countless hours discovering new places both local and abroad. It can be fun to start at your local airport, fly over your own home, and then abroad to locations you've visited before or perhaps completely new places. And of course... there are many types of planes to fly, and some are better at aerobatics than others. It's basically a violence-free reality-based video game. There's a little concern with the ability to talk to other users online, but I'll leave you to your own family's internet safety protocol for that one. Enjoy!

Please do add your own fabulous ideas in the comments. I'm always happy to hear about them, and so are other readers!